Hop Vine Moths, Hypena humuli

Hop Vine Moths, Hypena humuli

in a Wisconsin Cave

J. Mingari and Carroll Rudy

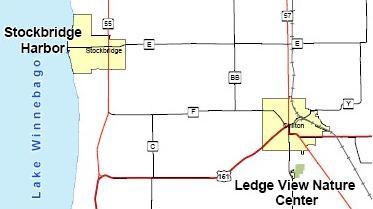

Ledge View Nature Center, Chilton, Wisconsin

Occasional Papers of the Moth Photographers Group

Number 1 - 30 October 2006

mothphotographersgroup.msstate.edu/Files/Live/CR/CaveMoths.shtml

People often see moths beating against their lighted windows at night, fluttering through headlight beams, making crazy circles around porch lamps. We even see moths during the day: kicked up from the grass, occasionally at flowers.

It's a serious moth-er, however, who sets out a fragrant buffet of alcohol and rotten fruit and then sneaks around in the night to photograph the beautiful moths dining there -- moths that are not usually seen at lights, or even in daylight. And it's a puzzled person who discovers moths while belly-crawling through the chilly, damp darkness of a cave.

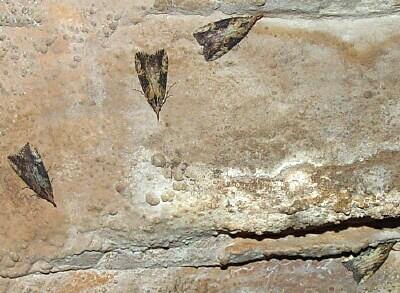

Yet there they were. Beaded with condensation, they clung to the cool limestone walls and ceilings, their tiny eyes shining like copper beacons in the flashlight's beam. They were a novelty to those who visited the caves. It took a few years to identify the moths simply because nobody ever remembered to bring a container for collection. When we did finally collect some specimens, they were not an easy ID: they were not shown in the Covell Field Guide to Moths of Eastern North America (1984). Their eventual identification raised more questions to be answered.

Yet there they were. Beaded with condensation, they clung to the cool limestone walls and ceilings, their tiny eyes shining like copper beacons in the flashlight's beam. They were a novelty to those who visited the caves. It took a few years to identify the moths simply because nobody ever remembered to bring a container for collection. When we did finally collect some specimens, they were not an easy ID: they were not shown in the Covell Field Guide to Moths of Eastern North America (1984). Their eventual identification raised more questions to be answered.

One room and two shafts of Mother's Cave, an unexcavated section of the dolostone (limestone) sinkhole cave system at Ledge View Nature Center held Hop Vine Moths, Hypena humuli.

Although it may seem somewhat unusual, it's not extraordinary to find moths residing in a cave. Amateur entomologist/photographer Bill Johnson of Minneapolis had photographed both Herald Moths (Scoliopterix libatrix) and Hop Vine Moths in caves in August 1998 (one of his photos is shown here, there are more below); and McKillop (1993) reported Heralds and Triphosa haesitata in Manitoba caves. Literature on Hop Vine Moths, however, appears to have focused on their damage to crops.

So why were the Hop Vine Moths in the cave? They were the only moths we've ever seen there.

According to Wagner et al.'s online draft Owlet Caterpillars of Eastern North America (see references), these moths are found in wet, mesic, or riparian areas. Was a drier- and hotter-than-normal summer driving the moths down into cool moisture?

According to Wagner et al.'s online draft Owlet Caterpillars of Eastern North America (see references), these moths are found in wet, mesic, or riparian areas. Was a drier- and hotter-than-normal summer driving the moths down into cool moisture?

Were they males or females? Ross H. Arnett's book, American Insects (1985), reported sexual dimorphism in coloration. Based on their color, our moths appeared to all be males. Were they engaged in an unusual kind of puddling in cave-wall condensation? No droplets were visibly being expelled. Meanwhile we hypothesized that they could be, instead, all females saving themselves for late egg-laying.

How much time did they spend in the cave? Why were they only in that limited area of a larger

interconnected cave system?

Determining gender was a challenge. Sexual dimorphism may be true of some Hypena humuli populations, but it was not in our population. Sexes could not be separated based on variations in color or pattern.

Seven moths were randomly collected from the cave for sexing. The moths were easily roused to

brief fluttering by a finger's touch, despite an average cave room temperature of 51ºF. Refrigeration did not slow them down enough to permit microscopic gender determination, so they were put in the freezer for two minutes, in order to brush scales off the last two abdominal segments and examine them. To our surprise, we had 4 males and 3 females. However, the two-minute freeze experience was fatal to five of the seven moths.

It was also noted that Hop Vine Moths came to lights in May and from late August through mid-September, so we speculated that the moths were using Mother's Cave for aestivation,

and we began formal observation of the moths in the cave on July 20, 2006. Our expectation was that the moths would leave the cave in late summer. Over the course of three months, 15 visits were made to count the moths, record the room temperature, and survey for signs of predation.

Mother's Cave is accessed via a narrow cleft halfway up a mossy north-facing bluff of Niagara

dolostone. It is surrounded by deciduous woodland, in which Sugar Maple (Acer saccharum), White Oak (Quercus alba), and White Ash (Fraxinus americana) are common trees. Non-woody plants around the cleft include Columbine (Aquilegia), Touch-me-not (Impatiens), and Clearweed (Pilea). Other cave system openings lie in exposed areas that tend to be hot, dry, and foot-beaten.

The first room of Mother's Cave, a.k.a. Propson's Room, is a chamber approximately 19 x 6 ft. with a ceiling varying from 1.5 to 2 ft. in height. It lies between and at the foot of two narrow, elbowed shafts. The back of the room is roughly 25 ft. into the ledge, and 9 ft. in depth from the opening cleft. Because of the cave's high dirt/breakdown floors, exploration is on one's belly, occasionally possible on hands and knees.

Though the moths are also found in uncertain numbers in the entrance shaft, and in far fewer numbers in the second, interior shaft, the count, beginning July 30, only concerned the 48 Hop Vine

Moths in the first room.

|

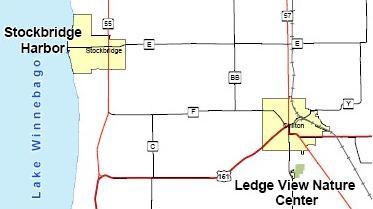

Mother's cave, so named because it was discovered on Mother's Day in 1986, is located in a mature deciduous hardwood forest in Ledge View County Park in Calumet County, Wisconsin. The entire north side of the park features a cliff outcrop of the Niagara Escarpment, one of many in Calumet County. The local name for these cliffs is "The Ledge." A cave entrance is just behind the large tree.

Mother's cave, so named because it was discovered on Mother's Day in 1986, is located in a mature deciduous hardwood forest in Ledge View County Park in Calumet County, Wisconsin. The entire north side of the park features a cliff outcrop of the Niagara Escarpment, one of many in Calumet County. The local name for these cliffs is "The Ledge." A cave entrance is just behind the large tree.

|

Mother's cave is but one cave in a system of interconnected sinkholes and "solution caves" in the park. The Cave's entrance is located in a crevasse several feet in depth located among rocks in the center of this photo. The hillside continues to slope downhill and northward over another escarpment into a large swamp where nettles probably serve as host plants for the larvae of the Hop Vine Moths.

Mother's cave is but one cave in a system of interconnected sinkholes and "solution caves" in the park. The Cave's entrance is located in a crevasse several feet in depth located among rocks in the center of this photo. The hillside continues to slope downhill and northward over another escarpment into a large swamp where nettles probably serve as host plants for the larvae of the Hop Vine Moths.

|

Relative humidity in that room was 91% in August, in spite of fresh airflow due to the cave system's seven openings. Temperatures in that room ranged from 49ºF to 52ºF over the study period. The most commonly recorded temperature was 50ºF. Temperatures tended to be stable and independent of outdoor variations. On July 25, 2006, for example, the room was 49ºF, while the outdoor temperature in woodland shade was 80ºF. A lot of human traffic temporarily raises the room temperature to 54ºF. As many as 1,000 visitors may pass through the cave and that room over the course of one year, mainly between May and October, usually in groups of 30 or less.

The moths shared their space with Cave Spiders (Meta menardi), an unidentified species of mosquito, an unidentified species of fly, unidentified gnats, probably Cave Crickets (Hadenoecus subterraneus) which are found elsewhere in the cave system, and also with insect-eating bats, whose visits were inferred from the regular appearance of fresh droppings.

By September 11, only 7 moths remained out of the original 48. In the meantime, moth wings appeared in little piles, and the Long-eared (Myotis septentrionalis) and Pistrelle (Pipistrellus

subflavus) Bats gradually returned as usual to the caves, where they were occasionally seen roosting or flying.

Predation was studied, as a possible explanation for the diminishing numbers of Hop Vine Moths in the room. Cave spiders continued to look well fed, but left no recognizable detritus, nor were moth mummies ever observed in the spiders' webs. Mice and Chipmunks have been seen in the cave, and empty nut and seed shells and nesting materials, such as are left by those animals, can be found tucked in corners and crevices of the cave system.

|

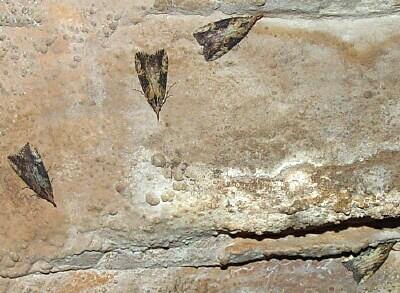

This view is straight up at the ceiling. The greyish white color similar to frost is due to limestone deposits. You can see some "Cave Coral" on the surfaces and edges of some rocks. The rocks are cracked and broken into the brick-like pieces because a layer of ice at least a mile thick lay on this bedrock once. When it melted, water flowed through crevasses, dissolving limestone as it went, and made caves.

This view is straight up at the ceiling. The greyish white color similar to frost is due to limestone deposits. You can see some "Cave Coral" on the surfaces and edges of some rocks. The rocks are cracked and broken into the brick-like pieces because a layer of ice at least a mile thick lay on this bedrock once. When it melted, water flowed through crevasses, dissolving limestone as it went, and made caves.

|

The water carried in volumes of mud, sand and gravel, scouring out the caves and leaving them partly filled with mud when the glaciers were gone. Animals have lived in these caves ever since. Propson's Room is shown here and is where the cave moths were counted. Keep in mind that the ceiling is only two to three feet above the floor in most places. You'd be crawling on your belly.

The water carried in volumes of mud, sand and gravel, scouring out the caves and leaving them partly filled with mud when the glaciers were gone. Animals have lived in these caves ever since. Propson's Room is shown here and is where the cave moths were counted. Keep in mind that the ceiling is only two to three feet above the floor in most places. You'd be crawling on your belly.

|

Fresh bat droppings were observed on each visit throughout Mother's Cave, including in Propson's Room. Because Long-eared Bats are known to glean (Ratcliffe/Dawson 2003), we looked for a method of determining the kinds of remnants left by different predators, particularly bats. Lacki (2000), in a study of Rafinesque's Big-eared Bats (Corynorhinus rafinesquii), reported that moth wings are discarded. Limited predation experiments using the nature center's captive Big Brown Bats (Eptesicus fuscus) and Pale Beauty Moths (Campaea perlata), and examination of the 12 moth wings found in the cave, led us to the hypothesis that the small piles of moth wings might be more likely a consequence of predation by rodents than by bats.

The Big Brown Bat predation experiment revealed that sometimes wings are discarded, and sometimes they apparently are eaten along with the body (they are missing). If they are discarded, it is not unusual to find puncture marks or ragged edges in them. Also, a lot of scales are rubbed off and it could be difficult to identify a moth based on the scale pattern of the wing. Finally, the wings are more or less scattered.¹

Twelve moth wings were found in Mother's Cave in Propson's Room and in the interior shaft. These included 4 forewings and 8 hindwings. They were always found in small piles, i.e., not scattered; they were always found within 3 inches of a wall; and they were often found on ledges or cave floor that came within 12 inches of the ceiling. They were difficult to collect due to moisture and gritty substrate. They were generally not ragged. They did hold some punctures or tears, which might also be a result of the difficulty in collection.

The wings we found in Mother's Cave retained enough scales for us to conclude that they did probably come from Hop Vine Moths, yet the quantity did not account for the declining moth population in the room or the cave. It seemed likely that the moths were leaving the cave per their usual flight period.

Census Counts in Propson's Room at Mother's Cave |

July 30

August 01

August 03

August 17

September 02

September 11

September 28

September 30

October 06

October 11

October 21

October 27

|

48

30

28

22

08

07

17

21

18

19

16

19

|

|

Notes: Counts are for moths seen only in Propson's Room. A very few moths were usually seen in the entrance tunnel where they might be crushed, and in the entrance chimney. Others might have been in crevices where they were impossible to include in the survey.

The late brood flight period began on August 25th.

On September 1st, seven moths were taken from the entrance tunnel for gender studies.

The first big cold front arrived on September 28th.

The late brood outdoor flight period ended on October 9th.

|

|

In late September an unexpected thing happened: As nighttime outdoor temperatures fell into the 30s the number of Hop Vine Moths began to increase in Mother's Cave, where the temperature remained stable. Would they now hibernate in the cave?

The draft publication by Wagner et al. states that Hypeninae overwinter as pupae in slight cocoons spun amongst leaf litter; however, the authors later state that Hypena humuli overwinters as an adult. Kikukawa (1982) reported these moths near the entrance of a Boone County, Missouri cave in January 1981.

We intend to continue to monitor the Mother's Cave population to see what we can learn.

Notes:

¹ Big Brown Bats have never been observed inside Mother's Cave, though they do use other parts of the cave system. Sleep/Brigham (2003) conclude that Big Brown Bats may not be able to glean due to their size and limited maneuverability in cluttered areas. Our experience with Big Brown Bats is that they must be taught to eat an insect off a surface with their mouth, otherwise they shove it into their tail membrane and attempt to eat it out of there, suggesting their primary feeding method is flight capture/hawking of flying insects. Moths in the cave were not observed in flight.

Mother's Cave was so named due to its discovery on Mother's Day in 1986. Propson's Room is named after Ms. Kim Propson, a member of the Wisconsin Conservation Corps, who was instrumental in the cave excavation work.

We thank Bill Johnson for photos taken at Redwing Cave in Minnesota, and other contributors to Moth Photographers Group who are identified beneath each photograph shown below.

J. Mingari is an Assistant Naturalist at Ledge View Nature Center. LedgeView@co.calumet.wi.us

Carroll Rudy is a retired biologist who continues her studies in natural history on 60 rural and wild acres that she shares with her husband near Chilton, Wisconsin. Here she can indulge her passion for rearing larvae and photographing them and adult moths. mcrudy@dotnet.com

|

Moths Mentioned in This Paper

|

|

|

References:

Adler, P.H. 1982. Soil- and Puddle-visiting Habits of Moths. Journal of The

Lepidopterists' Society 36(3): 161-173.

Arnett, R. H. 1985 (2nd. Ed. 2000). American Insects: A Handbook of the Insects of America North of Mexico.

Faure, P.A. 1993. The gleaning attacks of the Northern Long-eared Bat, Myotis septentrionalis, are relatively inaudible to moths. Journal of Experimental Biology 178: 173-189.

Kikukawa, S. 1982. An overwintering site of the Hop Looper, Hypena humuli (Harris). Entomological News 93(4).

Lacki, M.J. 2000. Effect of trail users at a maternity roost of Rafinesque's Big-eared Bats. Journal of Cave and Karst Studies 62(3): 163-168.

McKillop, W.B. 1993. Scoliopteryx libatrix (Noctuidae) and Triphosa haesitata (Geometridae) in caves in Manitoba, Canada. Journal of the Lepidopterists' Society 47(2): 106-113.

Ratcliffe, J.M. and J.W. Dawson. 2003. Behavioural flexibility: the Little Brown Bat, Myotis lucifugus, and the Northern Long-eared Bat, Myotis septentrionalis, both glean and hawk prey. Animal Behavior 66:847-856.

Sleep, D. J. H. and R. M. Brigham. 2003. An experimental test of clutter tolerance in bats. Journal of Mammology 84(1): 216-224.

Wagner, D., D. F. Schweitzer, J. Bolling Sullivan, and R. C. Reardon. Undated draft. Owlet Caterpillars of Eastern North America (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae).

|

Mother's cave, so named because it was discovered on Mother's Day in 1986, is located in a mature deciduous hardwood forest in Ledge View County Park in Calumet County, Wisconsin. The entire north side of the park features a cliff outcrop of the Niagara Escarpment, one of many in Calumet County. The local name for these cliffs is "The Ledge." A cave entrance is just behind the large tree.

Mother's cave, so named because it was discovered on Mother's Day in 1986, is located in a mature deciduous hardwood forest in Ledge View County Park in Calumet County, Wisconsin. The entire north side of the park features a cliff outcrop of the Niagara Escarpment, one of many in Calumet County. The local name for these cliffs is "The Ledge." A cave entrance is just behind the large tree.

Mother's cave is but one cave in a system of interconnected sinkholes and "solution caves" in the park. The Cave's entrance is located in a crevasse several feet in depth located among rocks in the center of this photo. The hillside continues to slope downhill and northward over another escarpment into a large swamp where nettles probably serve as host plants for the larvae of the Hop Vine Moths.

Mother's cave is but one cave in a system of interconnected sinkholes and "solution caves" in the park. The Cave's entrance is located in a crevasse several feet in depth located among rocks in the center of this photo. The hillside continues to slope downhill and northward over another escarpment into a large swamp where nettles probably serve as host plants for the larvae of the Hop Vine Moths.

This view is straight up at the ceiling. The greyish white color similar to frost is due to limestone deposits. You can see some "Cave Coral" on the surfaces and edges of some rocks. The rocks are cracked and broken into the brick-like pieces because a layer of ice at least a mile thick lay on this bedrock once. When it melted, water flowed through crevasses, dissolving limestone as it went, and made caves.

This view is straight up at the ceiling. The greyish white color similar to frost is due to limestone deposits. You can see some "Cave Coral" on the surfaces and edges of some rocks. The rocks are cracked and broken into the brick-like pieces because a layer of ice at least a mile thick lay on this bedrock once. When it melted, water flowed through crevasses, dissolving limestone as it went, and made caves.

The water carried in volumes of mud, sand and gravel, scouring out the caves and leaving them partly filled with mud when the glaciers were gone. Animals have lived in these caves ever since. Propson's Room is shown here and is where the cave moths were counted. Keep in mind that the ceiling is only two to three feet above the floor in most places. You'd be crawling on your belly.

The water carried in volumes of mud, sand and gravel, scouring out the caves and leaving them partly filled with mud when the glaciers were gone. Animals have lived in these caves ever since. Propson's Room is shown here and is where the cave moths were counted. Keep in mind that the ceiling is only two to three feet above the floor in most places. You'd be crawling on your belly.

©

©  ©

©  ©

©  ©

©  ©

©  ©

©